Now that Juneteenth is a federal holiday—and for many of us, a day off—it’s easy to see it as a great excuse to travel. But before you book that beach house or plan a long gay weekend, it’s worth taking a moment to understand why this day matters.

What Is Juneteenth?

Juneteenth—also known as Emancipation Day, Freedom Day, or the country’s second Independence Day—stands as an enduring symbol of Black American freedom. It marks the delayed but powerful enforcement of emancipation for enslaved Black Americans in Texas.

The History Behind the Holiday

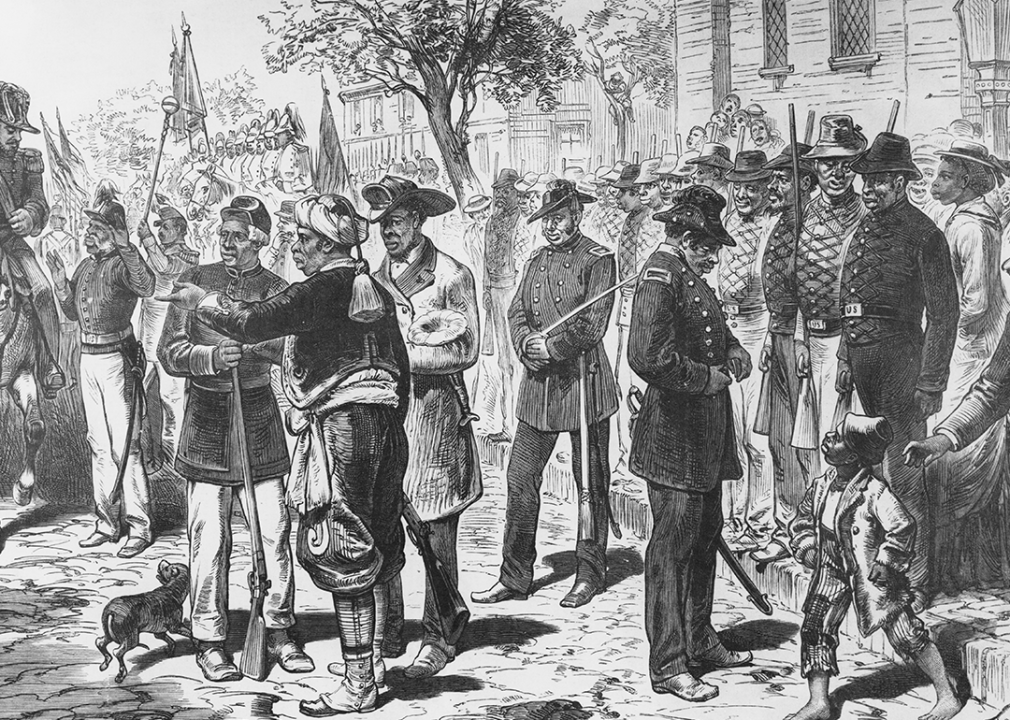

When Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger and fellow federal soldiers arrived in Galveston, a coastal town on Texas’ Galveston Island, on June 19, 1865, it was to issue orders for the emancipation of enslaved people throughout the state.

Although telegraph messages had spread news of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and while the Civil War had ended in the Union’s favor by April of 1865, Granger’s orders represented more than just a military update—they were a promise of accountability. There was now a large enough federal presence to enforce the end of slavery and to overturn the Texas Confederate constitution, which had explicitly forbidden the release of enslaved individuals.

In this way, Texas became the last Confederate state to end slavery in the United States.

From Local Celebration to National Recognition

Though Juneteenth has been celebrated for generations in parts of the U.S., its history and significance have only recently gained widespread national attention. The date wasn’t recognized as a federal holiday until 2021—more than 150 years after that momentous day in Galveston.

How Juneteenth Is Celebrated Today

Today, Juneteenth is commemorated with public art, festivals, and civic engagement across the country. In 2025, the long-awaited National Juneteenth Museum opened in Fort Worth, Texas, thanks to the tireless efforts of activist Opal Lee, often called the “Grandmother of Juneteenth.” Meanwhile, cities like Atlanta, Detroit, and Philadelphia continue to expand their Juneteenth programming with everything from economic justice panels to Black-led farmers markets.

A Day of Freedom—And a Call to Action

The holiday has also sparked renewed debates over how schools teach slavery and Reconstruction, especially amid rising restrictions on discussing race and Black history in classrooms.

As LGBTQ+ travelers, we know that freedom in this country has never been evenly distributed. Juneteenth is more than a day of remembrance—it’s a reflection of ongoing struggles for equity, visibility, and historical truth.

Why Juneteenth Still Matters

Here’s a look back at how Juneteenth came to be, why it still matters, and what we all need to remember—especially when we’re on the move.

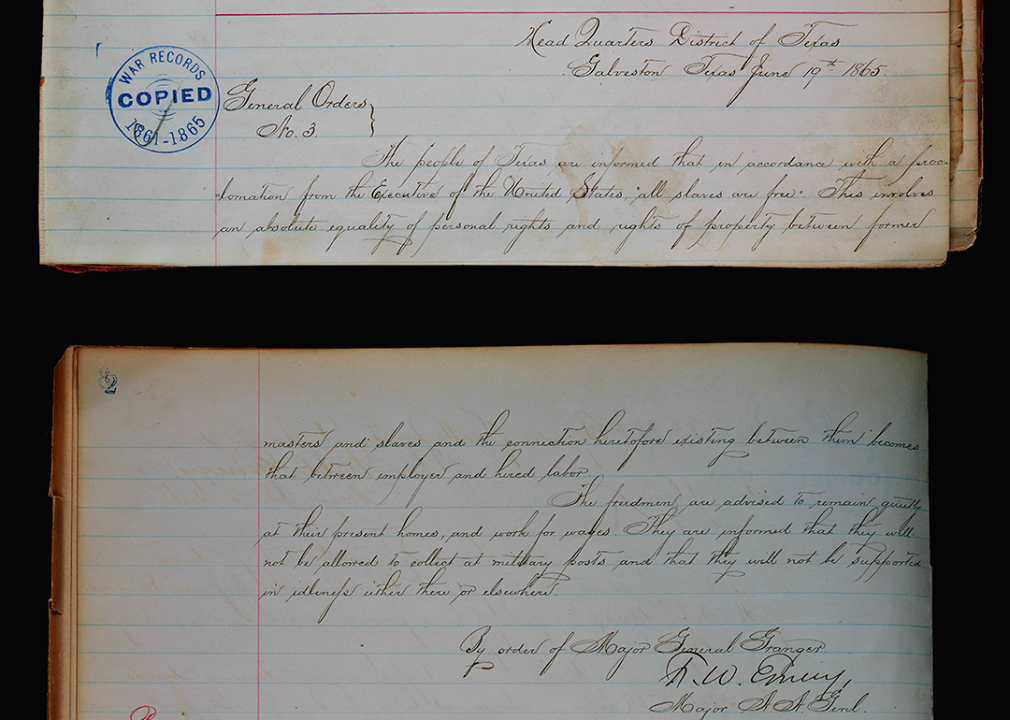

Juneteenth commemorates the 1865 delivery of General Order #3

Maj. Gen. Granger was given command of the District of Texas following the Civil War’s conclusion, making him an obvious choice for delivering General Order #3.

In its simplest terms, General Order #3 declared that all enslaved people in Texas were free; but the order maintained racist undertones and encouraged enslaved people to stay where they were being held to continue work—this time for wages as free men and women.

The order’s handwritten record, preserved at the National Archives Building in Washington D.C., reads:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They were told they couldn’t collect at military posts or be supported if idle there or elsewhere.

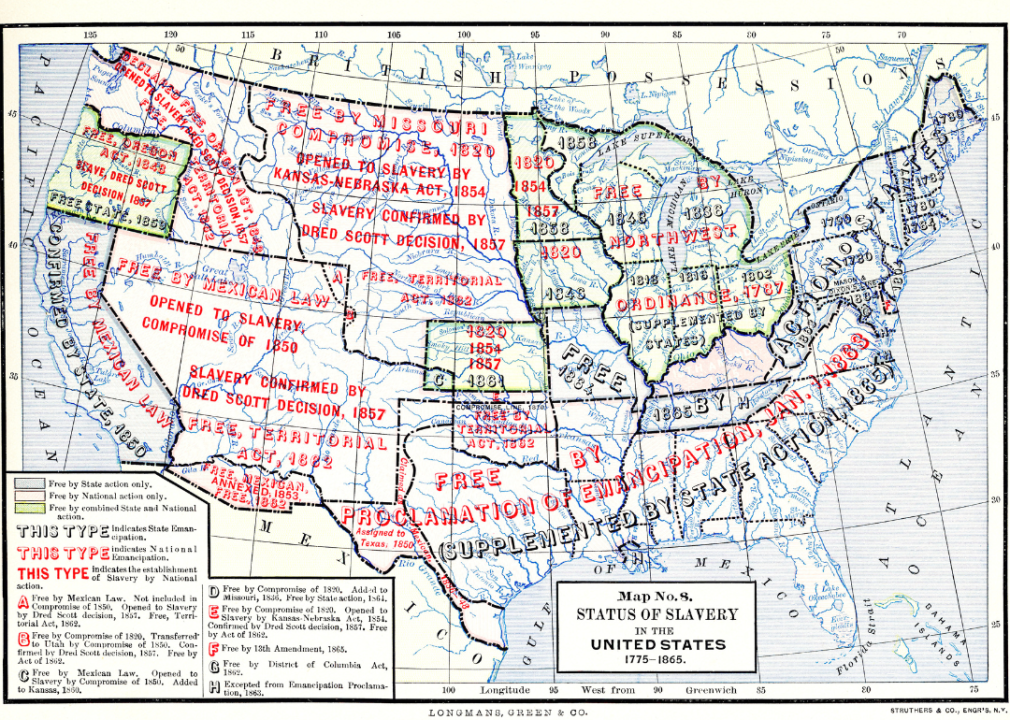

Chattel slavery in all states wasn’t abolished until the end of 1865

The Emancipation Proclamation, signed into law by President Lincoln on Jan. 1, 1863, called for an end to legal slavery in secessionist Confederate states only, impacting about 3.5 million of the 4 million enslaved people in the country at that time. As the war drew to a close and Union soldiers retook territory, enslaved people living in those areas were liberated.

Lincoln’s decision to free only those enslaved individuals in bondage in Confederate states was a strategic, militaristic method, as he notably did not free those enslaved in Union states. Further, the proclamation was unenforceable. Still, Union troops fighting in the war brought news of emancipation along with the military might to enforce it. Many enslaved people were motivated enough by the news to risk fleeing and seek safety in Union states or by joining the U.S. Army and Navy to help fight.

After the Emancipation Proclamation, enslaved people who escaped to Union lines were freed permanently.

Maj. Gen. Granger’s orders on June 19, 1865, released enslaved people in Texas from bondage. But it was another six months before the last two states—Delaware and Kentucky—freed enslaved people, and only when the 13th Amendment was ratified on Dec. 18, 1865.

The 13th Amendment officially ended slavery and involuntary servitude at the federal level, except as a punishment for a crime. That loophole has been capitalized upon since the amendment passed. Kentucky officially adopted the 13th Amendment in 1976.

Juneteenth celebrations originated in Galveston, Texas, starting in 1866

Mixed reactions followed Granger’s proclamation.

Many newly freed people worked for pay on former enslavers’ lands, while others moved north or to nearby states to reunite with family. As people fanned out around the country, they took Juneteenth celebrations along with them. Formerly enslaved people and their descendants also made yearly pilgrimages back to Galveston to memorialize the date’s significance.

Juneteenth became an official Texas holiday in 1980.

While Juneteenth is among the oldest celebrations of emancipation, it is not the oldest. That distinction goes to Gallipolis, Ohio, which has celebrated the end of slavery there since Sept. 22, 1863.

The first land to commemorate and celebrate the event was purchased in 1872 and is now a public park

In 1872, formerly enslaved Black ministers and businessmen raised $1,000 to buy 10 acres in Houston for Juneteenth celebrations. They called the lot Emancipation Park.

The park was donated to the city of Houston in 1916. In the late 1930s, the Public Works Administration, which was established as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, constructed a recreation center and public pool on the park site. The Houston City Council declared the park a protected historic landmark on Nov. 7, 2007.

Juneteenth has been celebrated in Mexico for more than 150 years

Mexico was a longtime sanctuary for those who escaped chattel slavery, with a Southern Underground Railroad that helped as many as 10,000 people flee bondage. Descendants of enslaved people who also emigrated over the southern border from the U.S. brought with them a tapestry of histories and traditions, including the Juneteenth celebration.

Juneteenth has been celebrated in a small Mexican village called Nacimiento since 1870.

The last enslaved people in the US weren’t adopted as citizens until 1885

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma sided with the Confederacy and included members who enslaved Black men, women, and children. Following the Civil War’s conclusion, the Choctaws did not grant those who were enslaved their freedom.

The Treaty of 1866 called for the Choctaws to free the enslaved Africans in exchange for $300,000 paid by the U.S. government to the Choctaws and the Choctaw Nation. Many of those liberated chose to stay and live as free people among the tribal communities. More than 100 years later, in 1983, Choctaw voters adopted a tribal constitution that declared all members “shall consist of all Choctaw Indians by blood whose names appear on the original rolls of the Choctaw Nation … and their lineal descendants,” all but expelling Freedmen citizens from citizenship within tribal communities.

Festivities became more commercialized in the 1920s during the Great Migration

Early Juneteenth celebrations focused on prayer and family, later expanding to rodeos, baseball, strawberry soda, and barbecues. Food has long been central to Juneteenth, as participants often arrive with their own dishes.

Juneteenth lost attention in the early 20th century as schools falsely taught that slavery ended solely with the Emancipation Proclamation.

Juneteenth officially became a Texas state holiday in 1980

Texas was the last Confederate state to end slavery—but the first to make Juneteenth an official state holiday.

The late Texas Rep. Al Edwards put forth a bill in 1979 called HB 1016 that was entered into state law later that year and went into effect on Jan. 1, 1980. It was more than a decade before another state—Florida—passed a similar law of recognition.

South Dakota was the last state to make Juneteenth a legal holiday

In February 2022, Gov. Kristi Noem signed HB 1025 to recognize Juneteenth as a legal holiday.

Hawai’i and North Dakota preceded South Dakota by about eight and 10 months, respectively.

Juneteenth wasn’t recognized as a federal holiday until 2021

Juneteenth achieved increasing recognition in recent decades, but the full embrace of the celebration as a national holiday gained momentum around the nation following the murder of George Floyd on May 20, 2020. The Black Lives Matter protests sparked nationwide corporate support for Juneteenth. From there, recognition of the holiday grew rapidly.

The following year, President Joe Biden signed a bill in June 2021 officially declaring Juneteenth a national holiday. Juneteenth was the first new federal holiday since 1983 (MLK Jr. Day) after decades of organizing.

This article was originally written by Nicole Caldwell with copy editing by Parid Close and published on Stacker.com. It has been edited by the fagabond team for fagabond.com.